Ancestry® Family History

Freedmen's Bureau Records & Freedman's Bank Records

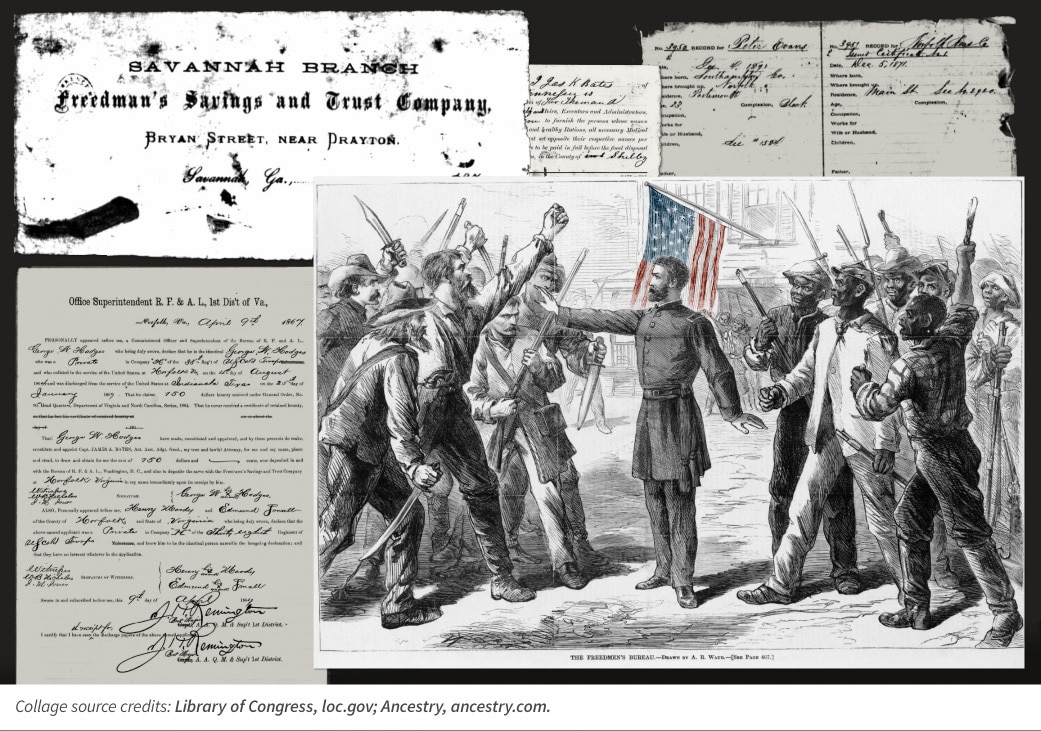

As the U.S. Civil War was ending and enslaved people were freed, President Lincoln and Congress established two important agencies to help formerly enslaved people transition from slavery to freedom: the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Freedman’s Bank.

For many African American family history researchers, the millions of documents created during the lifespan of these agencies can provide valuable insights into the lives of ancestors newly freed from enslavement. Freedmen’s Bureau and Freedman’s Bank records are likely the first time formerly enslaved African Americans appear in records after emancipation.

Before 1865, enslaved people in the United States couldn’t file official documents like marriage certificates, hold titles to land, register wills, or even be listed by name in federal censuses. They were usually not named in those records—now commonly used by people tracing their family roots—because they didn’t have the legal rights to file them. Before emancipation, the only time the names of enslaved people usually appeared in formal records was in inventory lists that were part of former enslavers’ wills and probate records, or in records regarding the financial transactions that governed their lives.

What Was the Freedmen’s Bureau?

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was established March 3, 1865. Its purpose was to provide aid in many different ways—food, housing, education, job support, and medical care, for example—to those formerly enslaved, to veterans of the U.S. Colored Troops, and to impoverished white people.

This agency was also part of the U.S. government’s overall plan for reorganizing the former Confederate states after the war, a period known as Reconstruction.

But the Act passed by Congress, formally called “An Act to establish a Bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees,” expired after a year. In 1866, Congress voted to extend the bill for two more years—overriding President Jackson’s veto. Funding for the Freedmen’s Bureau ended in 1872.

Where Did the Freedmen’s Bureau Operate?

The Freedmen’s Bureau only operated in these U.S. Southern states and Washington, D.C.:

- Alabama

- Arkansas (also includes Indian Territory [present-day Oklahoma])

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maryland

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- North Carolina

- South Carolina

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Virginia (also includes West Virginia)

If your ancestors might have lived near the border of one of these states, you may also want to check the records for that neighboring state.

And if you’re not sure whether your family has southern roots, keep in mind that before 1900, approximately 90 percent of Black Americans lived in the South. But during the Great Migration, between the 1910s and 1970s, millions of Black people moved north and west to urban areas like Chicago, New York, Detroit, and Los Angeles. This is why it’s so important to first trace your family locations back through the federal censuses. You may discover ancestors living in Chicago in 1920, who were born in Mississippi or Louisiana—states for which Freedmen’s Bureau records exist.

What Did the Freedmen's Bureau Do?

The Freedmen’s Bureau supported more than 4 million people during its relatively short existence. In its mission to provide immediate relief and support a path toward self-sufficiency, the agency focused on serving a wide range of needs by:

- Providing food rations and clothing

- Helping with employment-related services like witnessing job contracts or apprenticeship agreements and the disputes that arose due to them, and providing transportation to work sites

- Establishing schools and hiring educators

- Treating health conditions, illnesses, and diseases through new hospitals

- Awarding grants for land that had been confiscated by the government or deemed to be abandoned

- Writing letters on behalf of those who could not read or write

But probably the most personal and poignant role played by the Freedmen’s Bureau was trying to help people locate family members they’d been separated from during enslavement. Letters related to those searches are part of the Freedmen’s Bureau records.

Types of Records Created by the Freedmen’s Bureau

The Freedmen’s Bureau generated an incredibly wide range of records between 1865 and 1872. However, these records were not standardized, meaning that ration lists or employment contracts, for example, didn’t necessarily follow the same format across states—and sometimes even within a state. Similarly, not all records types may exist from one state to the next. In general, these are the kinds of documents that can be found in the Freedmen’s Bureau record collection.

Employment Records

- Employment registers

- Labor and employment contracts

- Apprenticeship agreements

Land Records

- Leases

Financial Records

- Tax assessments

Military Records

- Bounty awards

- Pension records

- Payments for military service

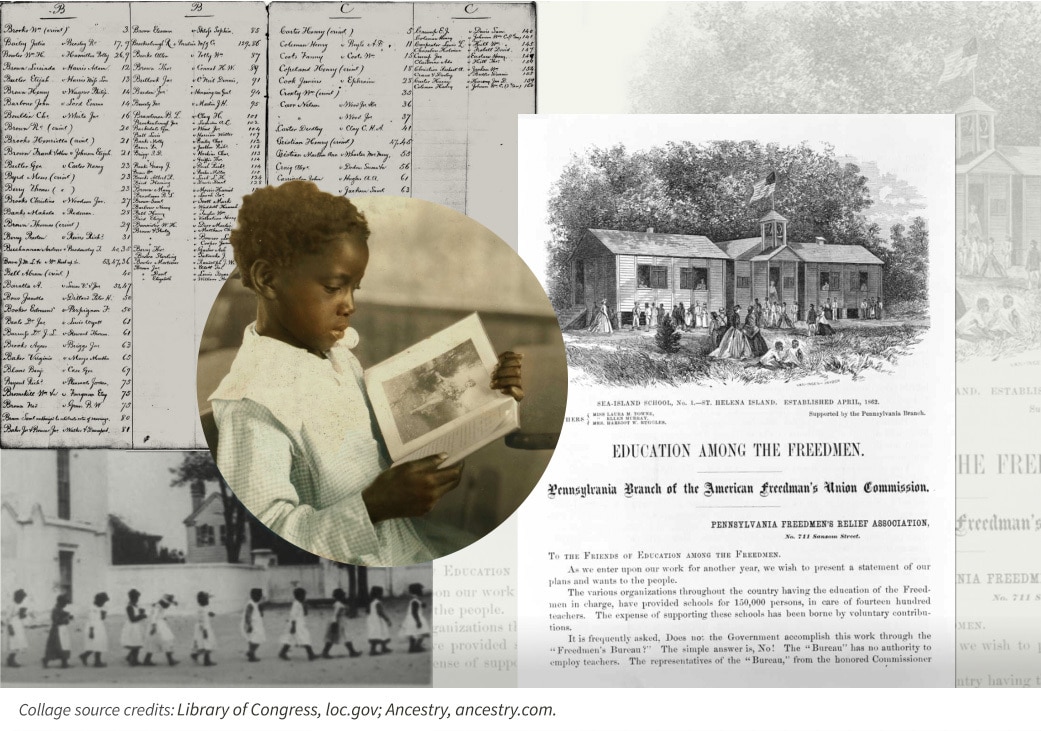

School Records

- Petitions to establish schools

- Student enrollment and attendance records

Other Records

- Ration lists

- Marriage records

- Court documents

- Hospital records

- Letters and other correspondence

- Local censuses

- Narrative reports

Preparing to Search for Your Ancestors in Freedmen's Bureau Records

Before you dive into these record collections, it can help to establish or review some facts about what you do and don’t know about your ancestors. And if you aren’t sure where to start, talk to your oldest family members to see what they know about your family history.

- Census records: Have you traced your family back to the 1870 census? If not, start with the 1950 census and work your way back in time. The information recorded in those U.S. census records can provide valuable clues for your search through Freedmen’s Bureau records. Make note of where someone lived, who was listed as living in the same household, the ages of family members, and their birthplaces. Tracing your family back through those records—as close as possible to the date of the Freedmen’s Bureau records—will help make sure you’ve found the right people.

- Pre-Civil War status: Do you know for sure whether your ancestors were enslaved at the time of the Emancipation Proclamation? Some African Americans lived freely or were manumitted before the Civil War ended—even in the South—which means they could appear in the federal 1860 census or earlier ones. African Americans who lived in northern or western states gained their freedom earlier, as states like Pennsylvania and Massachusetts passed laws in the late 1700s to gradually end slavery. By the early 1800s, all northern and western states had abolished slavery, although their laws vary in their timing and complexity.

- Surnames: Many enslaved people adopted (or were assigned) the surname of their former enslaver or the plantation where they worked. But others did have their own last names, which are likely to have been passed down by a parent. While these more personal surnames are less likely to be noted in pre-Emancipation Proclamation records, someone may have chosen to revert to their family surname after emancipation. They might also have chosen a new last name to distance themselves from their former enslaver.

An Important Legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau

Perhaps one of the most well-known legacies of the Freedmen’s Bureau—because it had the longest-term impact—was the founding of schools, often in collaboration with benevolent societies. Before the Civil War, due to laws against literacy amongst the enslaved, only about 10 percent of enslaved people in the South could read and write. So the establishment of schools by the Freedmen’s Bureau opened educational opportunities to many.

These new schools provided education at all levels, from primary grades through higher education. A number of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were founded during this time, including Shaw University in North Carolina and Fisk University in Tennessee.

Was the Freedman’s Bank Part of the Freedmen’s Bureau?

The Freedman’s Bank was separate from the Freedmen’s Bureau, but both agencies were authorized on the same day and with a similar goal: to work together to support the transition of formerly enslaved people and help them become self-sufficient. The Freedman’s Bank, formally known as the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, was to provide a safe place for people and organizations to deposit their money so they could grow their savings and begin to gain a stronger financial footing.

The bank, based in Washington, D.C., at one point grew to have dozens of branches across the country. During its existence, tens of thousands of people deposited their earnings—sometimes as little as $5 into an account—but the accumulated bank holdings from depositors reached millions of dollars. Despite the bank’s apparent success and rapid growth, the unstable post-war economy and the Panic of 1873 ultimately led to its collapse in 1874.

What Information Can You Find in Freedman’s Bank Records?

Like Freedmen’s Bureau records, Freedman's Bank records can include basic biographical details about account holders. For example, information on the account may note where the person was born and their current age; their race; the name of their spouse, parents, and children; their current residence; the name of their employer and current occupation; the name of a former enslaver; and whether they served in the military.

Exploring Freedmen’s Bureau and Freedman’s Bank Records on Ancestry®

More than 3.5 million names have been indexed from the Ancestry® record collections of the Freedmen's Bureau and Freedman's Bank, making it an incredibly important resource for those researching their African American family history.

Within these three collections, you may find rich details about individuals as well as families—information that can expand your family’s story.

- Freedmen's Bureau Records, 1865-1878

- Freedmen’s Bureau Marriage Records, 1846-1867

- Freedman's Bank Records, 1865-1874

Because there are many different types of records across and within these collections, you may discover information about your ancestor in multiple records. For example, you could find a teenager in school records as well as a hospital record. Or you might find an adult in an apprenticeship agreement or employment record as well as a bank record.

Also, the location of specific records may not always be intuitive. In the Freedmen’s Bureau collection, for example, you might find labor contracts in the Assistant Commissioner record group or requests for apprenticeships, pensions, or marriage records in the Records of the Field Offices.

Here are the different groups within the Freedmen’s Bureau collection:

- Records of the Field Offices: Local Bureau offices had the most direct contact with people in need. As such, these officials created or managed a wide variety of documents, like labor contracts, marriage certificates, relief rolls, censuses, letters, and affidavits from freed people as well as their employers. You may also find schooling information, land applications, trial summaries, and requests for legal aid and protection.

- Assistant Commissioner: While these are mostly narrative summaries and reports of state activities, they can still provide a wider perspective about the area in which your family lived. But tucked away in these records you might find detailed information like labor contracts and letters that pertain to a specific person who was receiving aid.

- Freedmen's Hospital and Field Offices: These contain daily reports about admissions and discharges from hospitals, which also include lists of patient names, ages, and health conditions.

- Office of the Commissioner: Letters in this group range for requests to confirm military service—in order to receive monetary bounties or pensions—to those that ask for help in reunifying a family.

- Superintendent of Education: This group has petitions for schools as well as overviews about schools in particular areas. You might learn whether the school your ancestor attended was funded by the Freedmen’s Bureau, a church, or a philanthropic organization.

Within the Freedman’s Bank collection, the different record groups have fairly self-explanatory titles. But it is worth noting that records in the “registers” group tend to contain the most biographical details about a person.

- Registers of Signatures of Depositors Dividend Payment Records

- Index to Deposit Records

- Loan and Real Estate Ledgers and Journals

- Miscellaneous Finance and Accounting Records

Note: While more than 3.5 million names from these record collections have been indexed, large portions of the collections still remain image only (i.e., not indexed). Non-indexed documents tend to be those that aren’t list based, such as letters and other correspondence. If you don’t find what you’re looking for through a traditional search, you may want to browse images from a particular record group or look for a specific document type.

Also, be sure to study closely the image of each document you review—even those that have been indexed—to check for details that may not have been transcribed. You might discover a valuable piece that adds to your family’s story.

The Freedmen's Bureau Records, Freedmen’s Bureau Marriage Records, and Freedman's Bank Records are available for everyone to search for free. You might just discover clues that could lead to a treasured family story. For example, in partnership with Paramount, Ancestry created the heartbreaking yet heartwarming film, A Dream Delivered: The Lost Letters of Hawkins Wilson, based on letters found in the Freedmen’s Bureau record collections.

References (all accessed June 7, 2023)

"A Brief Timeline of When Slavery Ended in the United States." The Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission. June 24, 2022. https://erlc.com/resource-library/articles/a-brief-timeline-of-when-slavery-ended-in-the-united-states/.

"African American Research at the Library of Virginia to 1870." Library of Virginia. https://lva-virginia.libguides.com/c.php?g=1162917&p=8489804.

"American Experience: Schools and Education During Reconstruction." WGBH Educational Foundation. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/reconstruction-schools-and-education-during-reconstruction/.

“Changing Names.” Facing History & Ourselves. May 12, 2020. https://www.facinghistory.org/reconstruction-era/changing-names.

Coleman, Colette. “How Literacy Became a Powerful Weapon in the Fight to End Slavery.” History.com. January 29, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/nat-turner-rebellion-literacy-slavery.

“The Freedman's Savings Bank: Good Intentions Were Not Enough; A Noble Experiment Goes Awry.” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://www.occ.treas.gov/about/who-we-are/history/1863-1865/1863-1865-freedmans-savings-bank.html.

“The Freedmen's Bureau.” African American Heritage. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/freedmens-bureau.

“The Freedmen's Bureau.” Educator Resources. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/freedmen.

“Freedmen’s Bureau.” History.com. October 3, 2018. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/freedmens-bureau.

“Freedmen’s Bureau Acts of 1865 and 1866.” United States Senate. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/FreedmensBureau.htm.

"Records of the Education Division of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands." U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/microfilm/m803.pdf.

Smith, Robyn N. “The Complexity of Slave Surnames.” Reclaiming Kin. March 14, 2017. https://reclaimingkin.com/the-complexity-of-slave-surnames/.