Ancestry® Family History

Finding Maiden Names

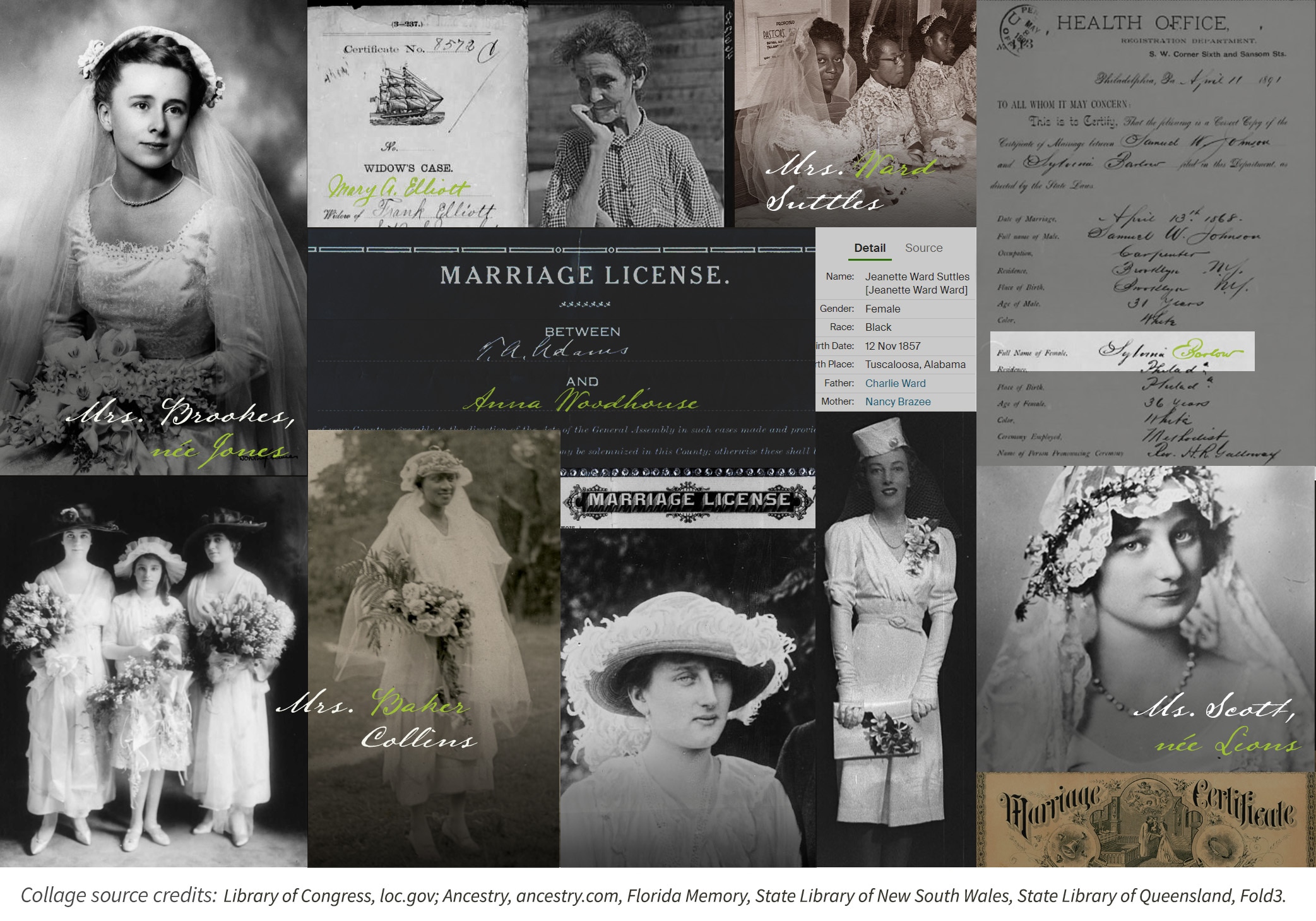

It’s common to start exploring your family history by looking for known family surnames. But you may run into a proverbial brick wall when you’re trying to discover your great-great-grandmother’s original last name—her maiden name. Who was “Mrs. Frank Smith,” “Widow Schaefer,” and “Mrs. Carmen Silva,” before marriage? What were their family names?

Why Knowing Maiden Names in Important

When you don’t know a woman’s maiden name—her last name before she married— it can make that branch of your family tree seem invisible. Yes, it’s usually easier to track paternal lines, because those surnames usually get passed down from one generation to the next. But if you only focus on paternal lines, you’re missing half of your fuller, richer family story.

Have Women Always Changed Their Last Name after Marriage?

The quick answer is “no.” But it could help your research to have a broader understanding of the complexity of the topic.

Cultures around the world have different laws and customs about a married woman’s last name, and those practices can change over time. Even if you start your search with U.S. records, at some point you may look for records from other countries. So be aware that surname practices can vary widely, based on the country, culture, and on when certain laws were passed.

Here’s a sampling of customs and laws across the globe:

- France: Since 1789, people have been legally required to use the surname on their birth certificate, but women may choose to use their husband’s name for social occasions.

- Mexico, Spain, and Chile: Women in Spanish-speaking countries haven’t traditionally changed their surname after marriage, but their children often carry a hyphenated surname—one that combines the last name of the father and the mother.

- Italy: Italian women, since 1975, have been prohibited from completely changing their last name when they marry, but they can add their husband’s surname to it.

- Japan: Spouses are not allowed to have different surnames, but they can choose which one to use.

- Germany: Women may keep their maiden name, adopt their husband’s surname, or choose a hyphenated version.

- Greece and Quebec: As of the late 1900s, laws required women to keep their maiden names.

- China, Korea, Malaysia: It has not been the custom for women to change their surname after marriage.

But historically, in many predominantly English-speaking countries, women have changed their surname after marriage. If you’re researching family members in the United States who married in the 17th, 18th, or 19th century, for example, it’s likely that a woman did adopt her husband’s last name. This isn’t true for Native Americans, however, as their customs can vary from one tribe to the next.

Reasons Discovering Maiden Names Can Be Tricky

A number of factors can complicate your search for maiden names in U.S. records. Still, being aware of the challenges could help you in the long run. Here’s what can add unexpected twists to your search.

- Timing: Vital records—birth, marriage, and death records—were required by different government bodies across the United States at different times. Unlike the United Kingdom, for example, which required civil registrations for birth starting in 1837 (England and Wales) and 1855 (Scotland), the United States did not have a nationwide system in place until roughly 100 later.

Before the 1940s, each state (or colony or territory) started requiring formal registration of “vitals” at different times. For example, you might find a 1680 Massachusetts town birth registration, but you wouldn’t find a government-required birth record for New York until 1880, at the earliest. Yet you could find an 1840 marriage record for Hawaii, even though Hawaii wasn’t a U.S. state at the time. - Inconsistent recording of facts: The information found in official records—especially early ones—can differ tremendously from one place to the next. You might see a maiden name on an early birth or death record, for example, and you might not. Until the 1940s, there wasn’t uniformity across the country in terms of what information was noted on a given legal document.

- Location changes: If a family moved from one county or state to another, and then relocated yet again, the “history” of the married woman’s birth family—including her maiden name—could have easily been left behind as the physical space between her and her original family increased.

You also might notice that your female ancestor’s birthplace is different from one record to the next. If so, you may have stumbled across a border change in the United States or Europe. For example, your great-great-great-grandmother may have been born in Virginia, but her death record says West Virginia. She actually may have lived in the same area her whole life, but the location change in the record suggests that she moved. Be sure you have a general understanding of the history of your target area, as it could affect where your desired records might be located. - Multiple marriages: It wasn’t uncommon in earlier days for a woman to remarry after her husband died, especially if she was widowed with young children, in order to provide stability for her family. But this second marriage could further obscure a woman’s maiden name. This is why witness names on official documents like wills can come in handy. You may discover that the witness is, in fact, her brother.

- Divorces: Unlike a name change after marriage, there’s no typical pattern for what happens after a divorce. Some women kept their married surname, while others chose to revert back to their maiden name, formally or informally.

- Changing cultural traditions: The United States is home to people from all over the world—some of whom may have kept in place naming traditions from their country of origin. Others may have adopted the norms of their new country after immigration.

Still, cultural practices shift over time. In the United States, up through the late 1900s, most women did choose to change their last name after marriage. Now, it’s more common to not change a name. And with the recent passage of laws allowing same-gender marriage, surname customs are likely to continue to evolve.

Which Records Contain Maiden Names?

A variety of record types could provide you with a maiden name. An official marriage record is the obvious starting point, but if you can’t find that document, then you’ll need to look for clues in other records. One of those hints could eventually help you uncover that elusive maiden name.

- Vital records. Birth, marriage, and death records are the natural place to find a woman’s maiden name. Sometimes those records even include the names of her parents and her mother’s maiden name.

Beginning in 1935, when people were able to obtain a unique ID from the Social Security Administration, the SSA became a de facto national birth registry—one that includes a woman’s maiden name. The Ancestry® Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 collection can be a rich resource of facts. You might even find an ancestor born in the 1850s, but who died in the 1930s. - The records of siblings. Because record formats were not standardized until the 1940s, information missing from one child’s record may still show up on that of another. If you’re not finding a maiden name for the mother of your ancestor, then check out the vital records or obituaries, for example, of one of the siblings.

- Church records. Baptism records often include the mother’s maiden name. In addition, they sometimes note the names of godparents or sponsors. Even if the relationship between a sponsor and a birth parent or child isn’t spelled out, the other people mentioned in the baptismal record may be relatives on the mother’s side of the family.

- First and Middle Names. Some family customs or cultural practices involve parents giving their child the mother’s maiden name as a first name. More common, however, is the use of a mother’s maiden name for the child’s middle name. (Think George Herbert Walker Bush.)

Other examples involve women who adopted their original family name as a middle name once they got married. While this convention is most commonly seen in more recent years, some women did adopt this practice earlier. (Think Elizabeth Cady Stanton or Shirley Temple Black.) - Probate Records. These records can sometimes be a very good resource for finding maiden names, as probates often spell out the relationships of heirs. Look especially for probate records and wills of relatives who died without heirs, as their siblings and the siblings’ children would then be next in line for inheritance.

- Other Court Records. Maiden names may also be found in court documents like applications for guardianship of a child, property disputes, divorce cases, or immigrant name changes, so make note of the other names you find on legal documents. Witnesses named in civil records may provide the connection to a woman's birth family, especially if you see a name recurring in multiple records.

Using those name clues, try searching for your ancestor in censuses in which she would have been a child using that surname. Paired with information you’ve found in later censuses after she was married, such as birth year and place, and the birth places of parents, you may be able to locate her. - Land Records. If your ancestor owned land, look to see how it was acquired. A woman’s father may have given or sold land to his daughter’s new husband at some point. And if a widowed woman was selling or bequeathing land (through a will), she could be transferring it to one of her surviving siblings or to another relative from her birth family. All of the names noted on a land record could provide either clear connections or be clues worth pursuing.

- Obituaries. Death notices and obituaries can be a great resource for finding maiden names. Even if a woman’s maiden name is not explicitly stated, through phrases like “born Smith” or “or "née Smith," the names of surviving relatives may reveal it. If her parents aren’t named, then what about brothers or sisters, nieces or nephews?

- Cemeteries. You may find a woman reunited with her family—parents and siblings—in the same cemetery plot or one nearby. If you can visit the cemetery in person, note the names on surrounding stones. You can also search a cemetery by plot location on Find a Grave®. Are any of the other names in that section familiar? They could match up with known relatives, sponsors, or witnesses.

- Military Pensions. When a widow applied for a pension, proof was required of the marriage. You may finally discover the woman’s maiden name in the marriage record or affidavit that was supplied. Look for military pension records on Ancestry® that include “widows” in the collection title. On Fold3®, you might review Civil War Widows’ Pensions or Navy Widows’ Certificates.

- Family Memorabilia. Treasured keepsakes like photo albums and scrapbooks may also help your search. You could find helpful notations on the backs of photos or even wedding announcements and funeral memorial cards. Your grandparents’ old address book, and notes on postcards and letters, could all have clues that point you to great-grandma's maiden name. And if you run across unfamiliar names, ask other family members what they know.

Tracing our female ancestors can be challenging, but luckily there are many different ways to tackle this often difficult hurdle. By exploring different types of records, you may learn even more about your ancestral lines as you build out your family tree.

Start your free Ancestry® trial today and see what you can discover about your maternal lines.

References

“Birth, Marriage, and Death Records.” New York State Archives. Accessed March 6, 2023. http://www.archives.nysed.gov/research/birth-marriage-death-records.

“Birth Certificates.” American Bar Association. November 20, 2018. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/publications/teaching-legal-docs/birth-certificates/.

Blakemore, Erin. “The History of Birth Certificates is Shorter Than You Might Think.” History.com. August 22, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/the-history-of-birth-certificates-is-shorter-than-you-might-think.

Evason, Nina. “German Culture, Naming.” Cultural Atlas. Accessed March 6, 2023. https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/german-culture/german-culture-naming.

Evason, Nina. “Mexican Culture, Naming.” Cultural Atlas. Accessed March 6, 2023. https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/mexican-culture/mexican-culture-naming.

“The Indian Act Naming Policies.” Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. March 11, 2014. https://www.ictinc.ca/indian-act-naming-policies.

Inuma, Julia Mio. “Japan says married couples must have the same name, so I changed mine. Now the rule is up for debate.” Washington Post. March 12, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/japan-names-marriage-women/2021/03/11/0fd38bca-7c30-11eb-8c5e-32e47b42b51b_story.html.

Koffler, Jacob. “Here Are Places Women Can't Take Their Husband's Name When They Get Married.” Time. June 29, 2015. https://time.com/3940094/maiden-married-names-countries/.

“Renaming Indians.” Native American Netroots. March 11, 2013. http://nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/1458.

Schoenberg, Nara. “After Marriage, More Women Using Their Maiden Name As Their Middle Name.” The Providence Journal. July 28, 2013. https://www.providencejournal.com/story/lifestyle/2013/07/28/20130728-after-marriage-more-women-using-their-maiden-name-as-their-middle-name-ece/35410522007/.