Ancestry® Family History

Puerto Rico

If you are Puerto Rican by origin, your DNA likely reflects a multiethnic genetic mix of Indigenous Taíno, African, and Spanish heritage. But when it comes to personal identity—like your name—the Spanish element in Puerto Rican surnames is prominent. Today, 99% of Puerto Ricans identify themselves as Latino—and the common Puerto Rican last names are Spanish.

As of 2021 U.S. Census Bureau figures show that almost 5.8 million people of Puerto Rican descent live in the U.S.—a 24 percent increase since 2010. About 3.1 million Puerto Ricans still live on the island.

A brief look at Puerto Rico’s history could provide context around your family's story—when the island was a colony of Spain, when it became part of the United States, and when the waves of migration to the U.S. mainland began.

Spanish Colonization of Puerto Rico

The lasting legacy of Spanish surnames began with the second voyage of Christopher Columbus to the so-called New World. This trip focused more on colonization instead of discovery. For example, as part of establishing new Spanish settlements, European livestock were brought on board.

On November 19, 1493, Columbus and his fleet reached an island, described by a witness as "most beautiful and appears very fertile." Called "Boriken"—meaning "the land of the brave lord"—in the Taíno’s Arawakan language, Columbus rebaptized it as "San Juan Bautista."

The Taíno and Importation of Enslaved Africans

It was on this island—now known as Puerto Rico—that Columbus first met the Taíno people, who represented the largest population of Indigenous people across the Caribbean islands. The Taíno people, who likely originated from the Orinoco region in South America, numbered about 30,000 people on this island at the time Christopher Columbus arrived.

As Spanish settlement began, workers were needed for the new plantations and gold mines, and native Taíno became a source of forced labor. But this enslavement meant that Taíno people’s own livelihoods suffered, leading to starvation and weakened immune systems, which couldn’t withstand the new European diseases. This combination devastated the Taíno community. A 1520 royal decree officially emancipated the enslaved Taíno, but by this time most of the Indigenous population had died. Within a few decades after the Spanish arrived, most of the distinct Taíno communities had gone. Their influences, however, are still present in Caribbean culture—music, religion, and language, for example.

To meet ongoing Spanish labor needs for tobacco, coffee, and sugar plantations, enslaved Africans were brought to the island, though at comparatively lower numbers than other islands in the area. This practice continued for several hundred years. During the 1800s, at least 50,000 additional Africans were brought to the island to support Spanish economic activities—three times more than were brought to the island during the previous 300 years combined. Slavery was finally abolished in 1873.

Puerto Rico Becomes a Possession of the U.S.

A growing independence movement led Spain to grant Puerto Rico significant autonomy in November 1897, and a bicameral legislature was created under a governor representing the Crown. Yet this arrangement would not last. In early 1898, the United States declared war on Spain after the U.S.S. Maine was sunk in a Cuban harbor.

A series of Spanish colonies—Santiago (Cuba), Manila (Philippines), and San Juan (Puerto Rico)—then fell, and the Spanish fleets were destroyed. Madrid admitted defeat. Through the Treaty of Paris in December 1898, Spain lost all its remaining colonies—and ceded Puerto Rico to the U.S.

New Governance for Puerto Rico

On the island, the first step the U.S. government took was establishing a civilian government under the Foraker Act of 1900. Efforts were also made to Americanize Puerto Rican statutes, culture, and institutions. But Puerto Ricans lost the autonomy they had recently gained under Spanish rule. And the island’s new designation as an "unorganized territory" meant that Puerto Ricans did not automatically become U.S. citizens. Ultimately, Puerto Ricans were granted U.S. citizenship through the Jones-Shafroth Act of 1917.

Puerto Rican Migration to the U.S. Mainland

The 1917 change in citizenship status enabled Puerto Ricans to travel or migrate anywhere in the United States. But despite the theoretical flexibility that citizenship provided, the reality of impoverishment and economic depression on the island in the late 1910s meant that few could afford the cost of travel to the mainland. The relatively modest initial wave of migration practically stopped during the Great Depression.

By the end of World War II, however, the situation changed—the Great Puerto Rican Migration had begun. This mass movement of people was the result of the U.S. government and the Puerto Rican government working together to accomplish two primary goals: address the mainland’s labor shortages and ease the island’s severely impoverished condition by encouraging migration. Thousands upon thousands of Puerto Ricans were motivated to seek new economic opportunities on the mainland.

New York City’s Puerto Rican population, for example, practically quadrupled between 1945 and 1946—from about 13,000 to more than 50,000. And the wave of migration continued, with more than a million Puerto Ricans moving to the mainland by the mid-1960s. While New York City gained the most new residents—other places in the Northeast, like Newark, New Jersey, Boston, and Philadelphia also saw their Puerto Rican populations increase.

Cultural Americanization and the Nuyorican Movement

As more Puerto Ricans migrated to the U.S. after World War II, their growing communities on the mainland began to vibrantly reshape places like New York City. And as Puerto Ricans mingled more with other Americans—through service in the Armed Forces, sports, acting, or music—Puerto Ricans made their way into America's mainstream.

One “mainstream” outcome was the enormously popular musical that highlighted Puerto Rican migration, West Side Story, which debuted in 1957. And the 1961 film adaptation was the second-highest grossing film that year. While some Puerto Ricans were insulted by their fictional portrayal, others appreciated the film’s acknowledgement of the discrimination they faced.

The term “Nuyorican"—coined from "New York" + "Rican" could have been used by islanders to describe the characters in that musical, as the moniker was originally a derogatory one used by islanders to describe those who had left Puerto Rico. Even today, the term remains controversial, with many still viewing it as a pejorative.

But beginning in the 1960s, New York City’s Puerto Rican community reclaimed the term as a way to show an identity distinct from the native islanders, the "Boricuas." The Nuyorican Movement of the 1960s and 1970s produced new intellectual ideas and cultural expressions that explored trans-cultural experiences through poetry, literature, the theater, music, and the visual arts.

Exploring Your Puerto Rican Heritage Through Ancestry® Records

Whether you’re trying to trace your Puerto Rican family’s migration to the U.S. mainland, or looking for pre-U.S. records about the island, a number of Puerto Rican record collections could provide new information about your family.

U.S. Census. Beginning with the 1910 U.S. Census, Puerto Ricans have been enumerated as part of the decennial count. If you’re just starting to research your Puerto Rican family history, you might begin with the 1950 census and then work your way back to the 1910 records. If you don’t know when your family migrated to the U.S., these documents could help you find your family’s first appearance on the mainland.

Census records in the 1900s also note an individual’s place of birth, so by looking at the birthplaces of a family group enumerated in one of these censuses, you might be able to narrow down the window for migration.

Immigration, Emigration, and Naturalization. Before—and sometimes despite—the Jones-Shafroth Act, many Puerto Ricans underwent the process of naturalization. If your family moved to the U.S. between 1897 and 1985, you might look for their files in the Federal Naturalization Records.

Other family members could have traveled back and forth between Puerto Rico and the mainland. These two collections could contain details about their movements:

- The record group, Passengers Arriving from Puerto Rico to the U.S. and Crew Lists (1901-1962), enables you to search by a person’s name or by ports such as Aguadilla, Fajardo, Ponce, San Juan, among others.

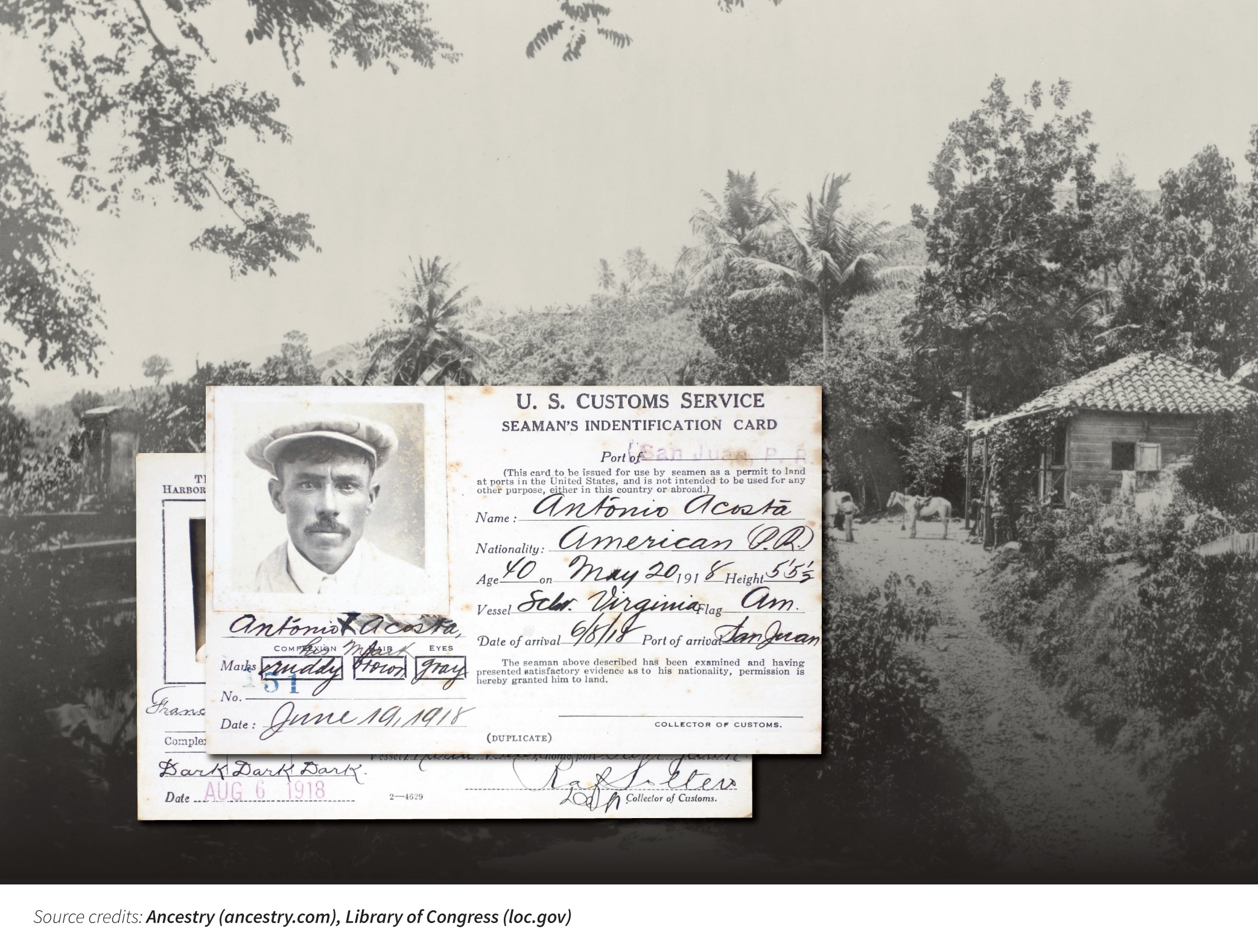

- And from 1916 onwards, Puerto Rican sailors were eligible for the Seaman's Protection Certificates, just like any other American sailor. Check the Applications received between 1916 and 1940. Details in these records include information such as an address, portrait, citizenship and more.

Military

If you know or think your Puerto Rican ancestors served in the U.S. military in the early to mid-1900s, there are several record collections to review.

- The U.S. Returns from Military Posts include records between 1806 and 1916. In addition to a name search, you can also select the post location “Puerto Rico” and a specific post name to see what records are available.

- The World War I and World War II Draft Registration Cards contain physical descriptions and next-of-kin names.

Vital Records before Puerto Rico became Part of the United States

If you’re looking for family records for the time when the island was still a colony of Spain, Puerto Rico Civil Registrations, which date from 1885, could contain birth, marriage or death accounts for your ancestors. Search by name, or browse by category or even location, like Arecibo or Bayamón, for example. Most genealogy-related files about the island will be in Spanish, so keep that in mind when you’re looking for early records.

If you're a Puerto Rican of African descent, you may find information about your ancestors in the database of enslaved people, the Registro Central de Esclavos, which the Spanish government created in 1872. But because enslaved people were usually only documented by a first name, these records can be challenging to use. It can help if you know the location where they might have lived, since enslaved people were listed accordingly.

How Dual Last Names Can Help Your Search

Puerto Ricans kept the Spanish dual last name custom in place. That's why people in Puerto Rico have two "apellidos." When it comes to genealogical research, this dual-name system can be a big help.

When a child is born, each parent passes on their first last name to the child, so the child gets a paternal and a maternal last name. For instance, in the case of María Sánchez-Rivera, "Sánchez" is her paternal last name and "Rivera" is her maternal last name. But because the U.S. system recognizes only one last name, it’s become common practice to hyphenate the dual surnames to avoid confusion with a middle name. (In recent years, the traditional order of the paternal and maternal last names is no longer obligatory as a way to underline gender equality.)

Learn Your Puerto Rican Family Story

Whether you’re focused on your Puerto Rican heritage on the U.S. mainland or searching for your roots on the island itself, the vast range of Ancestry® record collections could help you expand on your family’s story. You might even browse the U.S. Library of Congress Photo Collection to find historical images of the places where your relatives lived. Start your free trial on Ancestry® today and discover your family history.

Puerto Rico References (All sites accessed March 17, 2023)

Cabrera, Nicolas. “Dos Apellidos: When Families Have Two Surnames.” Denver Public Library History, November 17, 2020. https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/dos-apellidos-when-families-have-two-surnames.

Cheatham, Amelia, Diana Roy. “Puerto Rico: A U.S. Territory in Crisis.” Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/puerto-rico-us-territory-crisis.

“Chronology of Puerto Rico in the Spanish-American War.” Library of Congress. https://loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/chronpr.html.

“Citizenship and the American Merchant Marine: Seamen’s Protection Certificates, 1792–1940.” National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/naturalization/405-seamen-protection-certificates.pdf.

Dias De Fazio, Diane. “Introduction to Puerto Rico Genealogy: Names.” New York Public LIbrary. https://libguides.nypl.org/puertoricogenealogy/names.

“Exploring the Early Americas: Columbus and the Taino.” The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/exploring-the-early-americas/columbus-and-the-taino.html.

Flores, Lisa Pierce. History of Puerto Rico. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press, 2009.

Gibson, Samantha. “Puerto Rican Migration to the U.S.” Digital Public LIbrary of America. https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/puerto-rican-migration-to-the-us/teaching-guide.

“Jones Act.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/jonesact.html.

Krogstad, Jens Manuel, Jeffrey S. Passel, Luis Noe-Bustamante. “Key facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month.” Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/23/key-facts-about-u-s-latinos-for-national-hispanic-heritage-month/.

Lawler, Andrew. “Invaders Nearly Wiped out Caribbean's First People Long before Spanish Came, DNA Reveals.” National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/invaders-nearly-wiped-out-caribbeans-first-people-long-before-spanish-came-dna-reveals.

“Migrating to a New Land.” The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/puerto-rican-cuban/migrating-to-a-new-land/.

Minster, Christopher. “The Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus.” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/the-second-voyage-of-christopher-columbus-2136700.

Poole, Robert M. “What Became of the Taíno?” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2011. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/what-became-of-the-taino-73824867/.

“Puerto Rican Emigration: Why the 1950s?” Lehman College. https://lcw.lehman.edu/lehman/depts/latinampuertorican/latinoweb/PuertoRico/1950s.htm.

“Puerto Rican Migration Before World War II.” Lehman College. https://lcw.lehman.edu/lehman/depts/latinampuertorican/latinoweb/PuertoRico/beforeww2.htm.

“Puerto Rico.” Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/puerto-rico/.

“Puerto Rico.” US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/HAIC/Historical-Essays/Foreign-Domestic/Puerto-Rico/.

“Puerto Rico.” Yale University. https://gsp.yale.edu/case-studies/colonial-genocides-project/puerto-rico.

Román, Miriam Jiménez. “Boricuas vs. Nuyoricans—Indeed!” ReVista, May 18, 2008. https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/boricuas-vs-nuyoricans-indeed/.

Román, Iván. “Why Puerto Rican Migration to the US Boomed After 1945.” History.com. October 5, 2020. https://www.history.com/news/puerto-rico-great-migration-postwar.

“Rule by the United States.” Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Puerto-Rico/Rule-by-the-United-States.

“Society and the Economy in Early-Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico.” The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/collections/puerto-rico-books-and-pamphlets/articles-and-essays/nineteenth-century-puerto-rico/society-and-economy/.

Solomons, Gemma. “Becoming ‘Nuyorican’: The History of Puerto Rican Migration to NYC.” National Trust for Historic Preservation, October 13, 2017. https://savingplaces.org/stories/becoming-nuyorican-history-puerto-rican-migration-nyc#.Y0NRu3bMI2w.

Thomas, Hugh. Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire, from Columbus to Magellan. New-York: Random House, 2004.

“When Was Puerto Rico First Included in a Census of the United States? - History - U.S. Census Bureau.” United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/history/www/faqs/demographic_faqs/when_was_puerto_rico_first_included_in_the_us_census.html.

“The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War.” Library of Congress. https://loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/intro.html.