AncestryDNA® Traits

Vitamin E

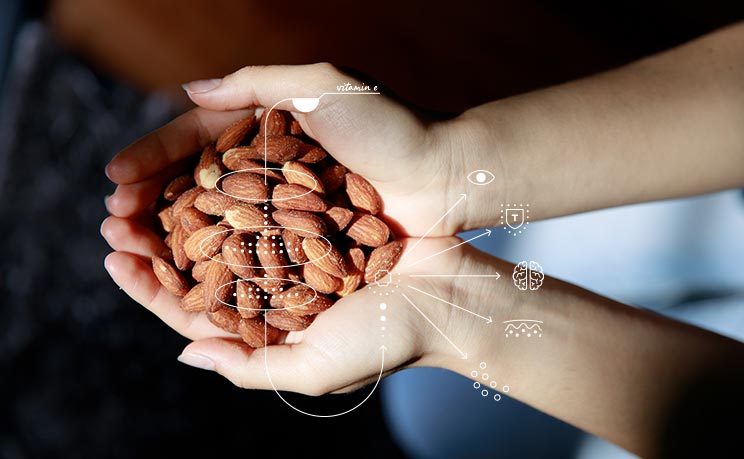

Vitamin E is an important nutrient for the function of many organs including the skin, brain, eyes, and blood. It is an antioxidant, helping to protect your cells from the effects of free radicals—reactive chemicals that can damage DNA. While your vitamin E levels are mostly influenced by the foods you eat, your genes may also play a small role. AncestryDNA® + Traits can tell you if people with DNA like yours tend to have typical vitamin E levels.

Vitamin E Benefits

Many of your organs, from your eyes to your blood to your skin rely on vitamin E to function properly. Vitamin E also enhances the body’s immune function, enabling it to fight off viruses and invading bacteria.

Like many vitamins, such as vitamin C and vitamin D, the benefits of vitamin E have been studied by a number of scientists in hopes of finding a connection to various health conditions.

Like many vitamins, such as vitamin C and vitamin D, the benefits of vitamin E have been studied by a number of scientists in hopes of finding a connection to various health conditions.

One interesting example of vitamin E research is heart disease. In clinical trials, vitamin E has not been shown to prevent coronary heart disease, the most common type of heart disease in the U.S. But some studies have suggested vitamin E could help prevent clots from forming in arteries, potentially playing a role in reducing the risk of life-threatening blood clots in other parts of the body, such as the legs and lungs.

What vitamin E is perhaps best known for, however, is its role as an antioxidant. As an antioxidant, it helps protect your cells from damage caused by free radicals. These are compounds that your body is exposed to in the environment (such as UV light, tobacco smoke, or air pollution), or that are naturally formed when your body processes food.

Vitamin E Deficiency

Vitamin E deficiency is very rare in the U.S. And those who do have a deficiency in vitamin E are most likely to have a health condition that impairs the body’s ability to properly digest or absorb fat. Examples include pancreatitis, Crohn’s disease, and celiac disease—as well as rare inherited conditions such as cystic fibrosis and abetalipoproteinemia.

The connection between an impaired ability to absorb or process fat and a deficiency in vitamin E is that as a fat-soluble nutrient, vitamin E relies on fat for the digestive system to absorb it.

Like other fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin E is usually absorbed in fat globules that travel through the small intestines into the body’s circulatory system. It is then largely stored in the liver, where it is repackaged and secreted again into the blood.

Some signs of vitamin E deficiency include muscle weakness, vision impairment, loss of control of body movements, including difficulty walking, and a weakened immune system.

While vitamin E levels are largely influenced by the foods you eat, AncestryDNA® looks at four markers that may be associated with slight differences in vitamin E levels, one located in each of the following places:

- near the BUD13 and ZPR1 genes on chromosome 11

- in the TTPA gene on chromosome 8

- in the CYP4F2 gene on chromosome 19

- in the SCARB1 gene on chromosome 12

Sources of Vitamin E

Vitamin E can be found in a range of foods. Some sources of vitamin E include:

- Nuts (such as peanuts, hazelnuts, walnuts, and especially almonds)

- Seeds (such a sunflower seeds or pumpkin seeds)

- Vegetable oils (such as wheat germ, sunflower, safflower, and soybean oil)

- Leafy, green vegetables (such as spinach and collard greens)

- Red bell peppers

- Mangos

- Avocados

In addition, some food manufacturers add vitamin E to their processed foods. Some examples of vitamin-fortified foods include breakfast cereals, margarines and other spreads, and fruit juices. Consumers should check the product labels to find out which ones have vitamin E, and how much.

The amount of vitamin E you need varies by age, but the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for vitamin E for people 14 and older is 15 milligrams per day. Women who are breastfeeding need a bit more vitamin E; they have an RDA of 19 milligrams a day.

Most people in the U.S. get their RDA of vitamin E without having to take supplements.

For instance, the combination of foods below could help you get over 15 milligrams of vitamin E:

- One cup of dry roasted peanuts (7.2 mg)

- Two tablespoons of sunflower seed butter (7.32 mg)

- One cup boiled, mashed sweet potato (3.08 mg)

Interesting Facts about Vitamin E

When many people think of vitamin E, they may think of a single compound that is found in various foods and can also be taken in supplements.

But the term “vitamin E” is actually a term for eight different compounds (four tocotrienols (α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocotrienols) and four tocopherols (α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocopherols). Of these eight naturally existing forms of vitamin E, only one is used by the human body: alpha-tocopherol.

All eight forms of vitamin E are absorbed by the body in the same way, through the small intestine, and then stored largely in the liver. But the liver then redistributes only alpha-tocopherol back into the blood for use by the body. The other forms are excreted.

In addition to natural sources of vitamin E, there are also synthetic forms. On food packaging and supplement labels, vitamin E from natural sources is often listed as “d-alpha-tocopherol.” Synthetic vitamin E is listed as “dl-alpha-tocopherol.”

Natural vitamin E is more powerful; it takes two milligrams of synthetic vitamin E to equal one milligram of natural vitamin E.

References

Boyles, Salynn. “Vitamin E May Lower Blood Clot Risk.” WebMD, September 10, 2007. https://www.webmd.com/women/news/20070911/vitamin-e-may-lower-blood-clot-risk.

Lee, Ga Young, and Sung Nim Han. “The Role of Vitamin E in Immunity.” Nutrients. MDPI, November 2018. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/nu10111614.

Major, Jacqueline M., Kai Yu, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Three Common Variants Associated with Serologic Response to Vitamin E Supplementation in Men.” The Journal of Nutrition, March 21, 2012. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.156349.

Major, Jacqueline M., Kai Yu, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Common Variants Associated with Circulating Vitamin E Levels.” Human Molecular Genetics, July 5, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddr296.

Richards, Louisa. “What to Know about Vitamin E.” Medical News Today, January 4, 2021. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/vitamin-e#top-sources.

Schmölz, Lisa, Marc Birringer, et al. “Complexity of Vitamin E Metabolism.” World Journal of Biological Chemistry, February 26, 2016. http://doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v7.i1.14.

Silver, Natalie. “How to Identify and Treat a Vitamin E Deficiency.” Healthline, September 18, 2018. https://www.healthline.com/health/food-nutrition/vitamin-e-deficiency#what-you-can-do.

“USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference: Vitamin E.” NIH. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/VitaminE-Food.pdf.

“Vitamin E and Skin Health.” Linus Pauling Institute. Oregon State University. Accessed July 1, 2021. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/health-disease/skin-health/vitamin-E.

“Vitamin E Fact Sheet for Consumers.” National Institutes of Health (NIH), November 20, 2020. https://ods.od.nih.gov/pdf/factsheets/VitaminE-Consumer.pdf.

“Vitamin E.” Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, May 13, 2021. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/vitamin-e/.