Ancestry® Family History

Works Progress Administration (WPA)

Americans have rarely experienced as much hardship as they did during the Great Depression. In the 1930s, many lost their jobs, homes, and savings, and were forced to wait in bread lines and live in shantytowns.

Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Works Progress Administration. Together, these programs are known as the New Deal.

Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Works Progress Administration. Together, these programs are known as the New Deal.

At a time when as much as a quarter of the labor force was unemployed, the New Deal put millions of Americans to work. They took on a wide range of projects, from building the Hoover Dam to collecting oral histories, planting trees, and enhancing public buildings. This federally funded effort also produced extensive records that are a rich resource for family historians, especially those created by the WPA.

Notable WPA Projects

The Works Progress Administration (also called the Work Projects Administration), launched in 1935, replacing the Emergency Relief Administration, and it created jobs for both skilled and unskilled workers. The WPA employed over 8.5 million Americans on 1.4 million projects until it was disbanded in 1943. Jobs paid an average salary of $41 per month (less than $900 in today's dollars)—just enough, the government hoped, for people to subsist and maintain their self-respect. Most jobs involved manual labor, like building roads and bridges. But WPA programs also involved creating projects for people in the arts and education.

The Federal Writers' Project hired thousands of writers to produce state guidebooks and collect the life stories of ordinary Americans, including formerly enslaved people. Some Federal Writers later became famous, like Saul Bellow, John Cheever, Zora Neale Hurston, and Ralph Ellison.

The Federal Theatre Project put on plays and musicals across the country, staged shows by young playwrights, and presented radio dramas. It supported about 10,000 theater professionals, including Orson Welles, who in 1936 directed a sensational staging of Macbeth in New York under the program's auspices.

The Federal Art Project hired artists and arts educators to paint murals, make sculptures for public buildings across the country, as well as open community art centers. They also designed and painted signs, like the WPA National Park posters. Jackson Pollack, Lee Krasner, and Mark Rothko were among the approximately 10,000 artists the program employed.

The Federal Music Project put on free concerts, funded orchestras, offered music lessons, and commissioned original compositions.

The Historical Records Survey hired thousands of people to fan out across the country, scour public archives, and create an inventory of federal, state, and municipal records.

Other New Deal Agencies

The WPA is perhaps the most famous of the so-called "alphabet soup" agencies of the New Deal, but many others put Americans to work as well.

The Tennessee Valley Authority was established in 1933 to control floods and improve navigation along the Tennessee River, as well as produce electrical power by building dams and generators. It lifted up an economically depressed region spanning parts of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Virginia.

The Civilian Conservation Corps hired young single men to improve the country's public lands. Between 1933 and 1942, they planted over two billion trees, built hiking trails, fought forest fires, and helped control erosion. The program provided meals and lodging and sent most of the workers' pay straight to their families. It also published an internal newspaper, Happy Days, that is available to browse on Ancestry®. The newspaper included project notes and articles about workers' accomplishments and heroic deeds.

The Farm Security Administration was behind many of the most iconic photographs from the Depression years. Created to fight rural poverty through loans and farm management programs, it is best known for sending photographers into the field to document the lives of sharecroppers and migrant workers. Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks are among those who helped bring attention to the plight of rural laborers.

Where to Look for WPA Records

Many of the most useful WPA records were compiled by the Historical Records Survey, which indexed public records held in places like churches, county clerks' offices, or courthouses. There are also oral histories conducted by the WPA, meaning you might be able to find a detailed account of your ancestor's life. Here are some places where you can access these WPA records:

Vital Records: The HRS indexed vital records, like birth, marriage, and death certificates, many of which are now searchable on Ancestry. In Indiana, for instance, the HRS indexed birth and death records from 1880 to 1920, and marriages from about 1850 to 1920. Vital records cover key genealogical information like name, gender, race, birth date, and parents' names.

Naturalization Records: The HRS worked on several naturalization collections. These records may include details like a person's country of origin, alternate spellings of their name, current residence, or even a physical description. One of the most valuable is the Philadelphia Naturalization Records from 1789 to 1880, which includes information on over 113,000 immigrants in the city who applied for citizenship. In Massachusetts, the HRS helped compile records dating to 1798.

Cemetery Inscriptions: Charles R. Hale led a WPA project that transcribed inscriptions on headstones in 2,000 cemeteries in Connecticut. Dating from 1629 to 1934, these records include names, dates of birth and death, and burial place. Some also mention names of spouses and children.

Narratives of Formerly Enslaved People: The Civil War was still in living memory for older Americans at the time of the New Deal. People working for the Federal Writers' Project collected first-person accounts of slavery, talking with over 2,300 formerly enslaved African Americans. The database, "Interviews with Formerly Enslaved People, 1936–1938" contains their names, ages, and birthplaces, as well as their personal history and sometimes a photo. This amazingly rich collection is especially important given how difficult it can be to find records of formerly enslaved people.

How to Find Family in WPA Records

It can be hard to find out if your ancestors worked for the WPA. There's no single directory of every person involved, so you may have to do some sleuthing. However, given that the WPA and other New Deal agencies employed millions of Americans, there's a good chance someone in your family benefited from the programs. Here's how to begin your research:

Look Up Your Family Members In the 1940 Census: If they were of working age, check under occupation and industry. You may find "WPA" listed as their industry, with an occupation like laborer, road worker, housekeeper, or artist. The census also asked people their salary, so you can discover how much money your ancestor earned with the agency. The entries for Dorothy West and Ralph Ellison, for instance, both said they were writers with the Federal Writers' Project and made over $900 in 1939.

See If They Worked For the Government: The 1940 Census asked everyone over 14 if they had worked for the government during the previous week. Question 22 specifically asked if they did public emergency work with an agency like the WPA during the week of March 24 to 30, 1940. If your ancestor answered yes, they probably worked for a New Deal agency. But this question only refers to a single week, so if they answered no, your relative may have still worked for the WPA at another time.

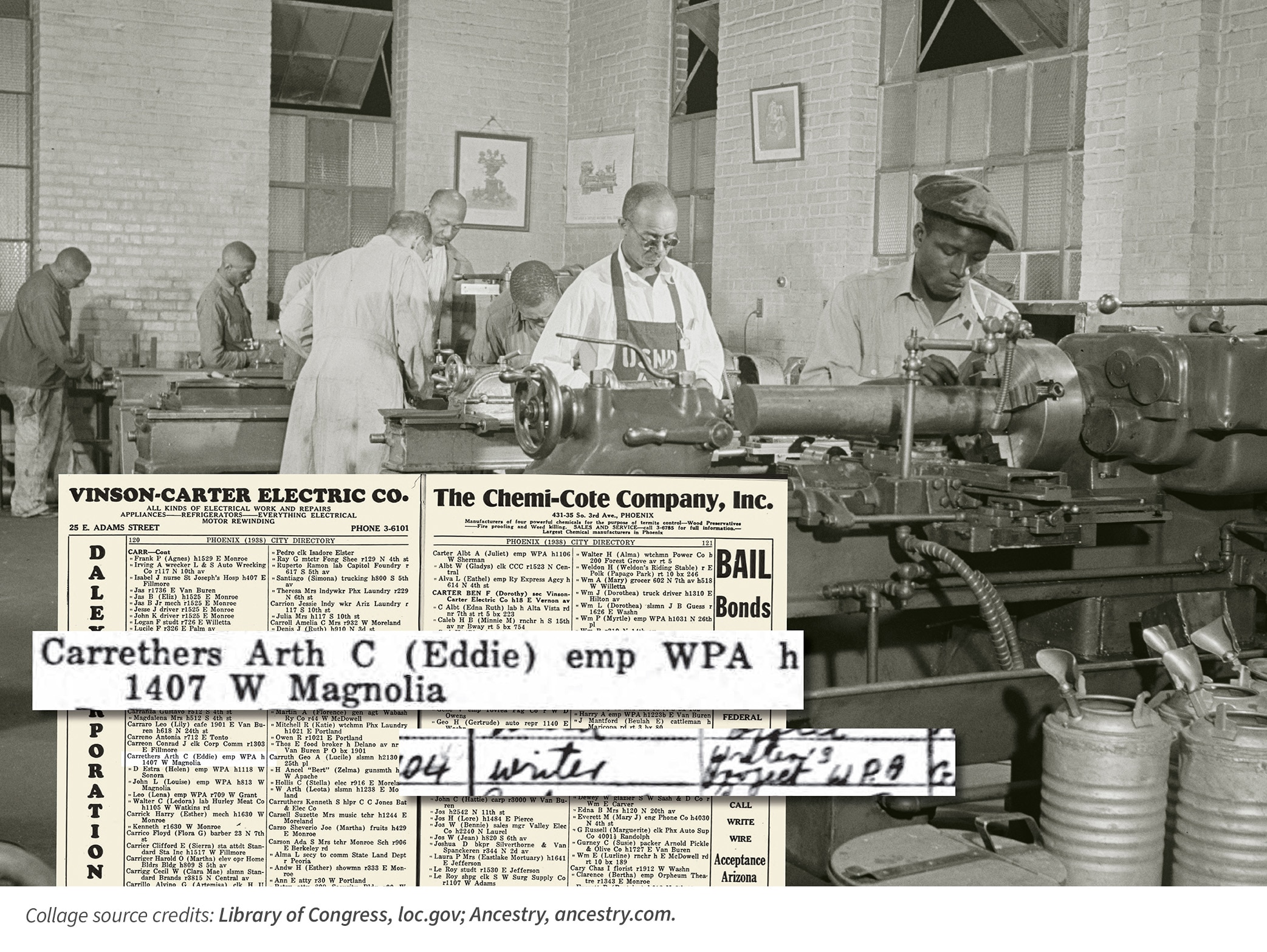

Consider Their Occupation: Certain jobs might indicate that your ancestor had a New Deal job at some point in the 1930s. Check both the 1940 and 1950 censuses for leads. For example, if they worked in flood control in Tennessee, maybe they got their start at the Tennessee Valley Authority. A park ranger in the West might have been part of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Librarians, teachers, and archivists could have been employed by the Historical Records Survey; actors by the Federal Theater Project; and conductors by the Federal Music Project. Anyone who did manual labor in 1940 was likely involved in one of the many public works projects of the previous decade.

Consider Their Occupation: Certain jobs might indicate that your ancestor had a New Deal job at some point in the 1930s. Check both the 1940 and 1950 censuses for leads. For example, if they worked in flood control in Tennessee, maybe they got their start at the Tennessee Valley Authority. A park ranger in the West might have been part of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Librarians, teachers, and archivists could have been employed by the Historical Records Survey; actors by the Federal Theater Project; and conductors by the Federal Music Project. Anyone who did manual labor in 1940 was likely involved in one of the many public works projects of the previous decade.

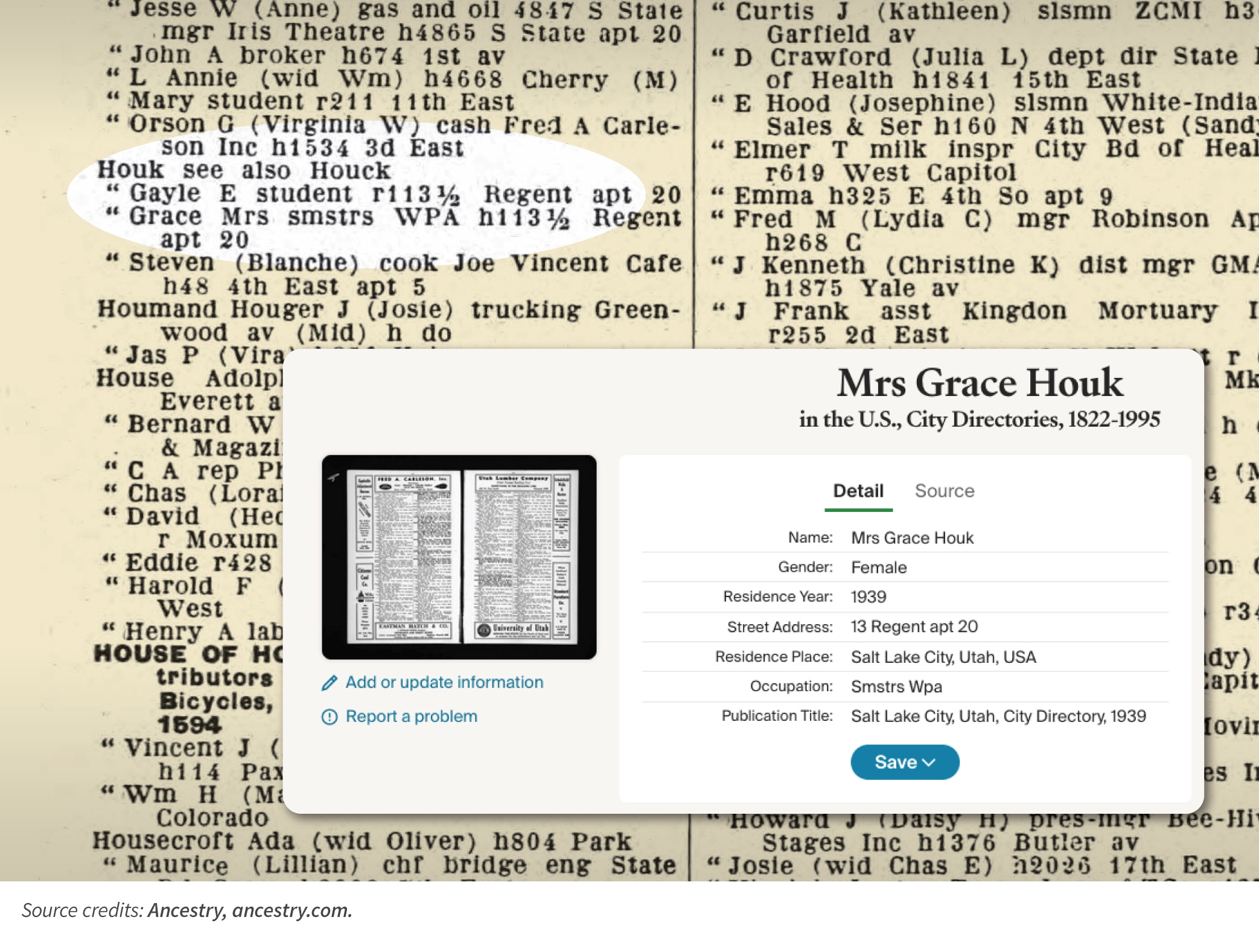

Search City Directories: The precursor to phone books, city directories listed names, addresses, and sometimes occupation. Your ancestor may have listed their employer as "WPA," or something more specific, like "seamstress WPA." Or maybe one of your ancestors lived somewhere that had been built by the WPA. A telltale clue would be if the listed address was something like "31 WPA Cabins" or "1982 WPA Road."

Check Employment Directories: Employee cards and directories can also provide leads. Search keywords like "WPA" and "public works" to see if your ancestor was involved in building highways or another infrastructure project.

Find out how the New Deal and the WPA impacted your family. By exploring historic newspapers, vital records, the 1940 and 1950 censuses, and photos from the era, you may learn new information about your family’s history. Discover your family story on Ancestry® and Newspapers.com® today.

References

"American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1940 (Introduction).” The Library of Congress. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/collections/federal-writers-project/articles-and-essays/introduction/.

"Artists of the New Deal.” History.com, September 13, 2017. https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/artists-of-the-new-deal#section_5.

Berger, Erin. "Meet the National Parks' 'Ranger of the Lost Art'.” The New York Times, August 25, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/25/style/ranger-doug-leen-wpa-national-park-posters.html.

Bernstein, Irving. "Chapter 5: Americans in Depression and War .” United States Department of Labor. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/chapter5.

"The Civilian Conservation Corps.” National Parks Service. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-civilian-conservation-corps.htm.

"CPI Inflation Calculator.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

"Essay: The Federal Emergency Relief Administration.” University of Washington. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://content.lib.washington.edu/feraweb/essay.html.

"Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives (About This Collection).” The Library of Congress. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/collections/fsa-owi-black-and-white-negatives/about-this-collection/.

"Federal Emergency Relief Act of 1933.” Social Welfare History Project. Virginia Commonwealth University. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/great-depression/federal-emergency-relief-act-of-1933/.

"Federal Theatre Project, 1935 to 1939: The Play That Electrified Harlem.” The Library of Congress. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/collections/federal-theatre-project-1935-to-1939/articles-and-essays/play-that-electrified-harlem/.

"History of USDA's Farm Service Agency.” USDA. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.fsa.usda.gov/about-fsa/history-and-mission/agency-history/index.

Little, Becky. "9 New Deal Infrastructure Projects That Changed America.” History.com, April 7, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/new-deal-infrastructure-projects-fdr#.

"New Deal.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/event/New-Deal.

"President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal.” The Library of Congress. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/franklin-delano-roosevelt-and-the-new-deal.

"Questions Asked on the 1940 Census.” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://1940census.archives.gov/questions-asked.asp.

"Tennessee Valley Authority.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tennessee-Valley-Authority.

Thompson, Lisa. "Historical Records Survey (HRS) (1935).” Living New Deal, November 18, 2016. https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/historical-records-survey-hrs-1935-1943/.

"Today in History - April 8: Works Progress Administration.” The Library of Congress. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/april-08/.

"The Work of the Civilian Conservation Corps : Pioneering Conservation in Louisiana.” The Library of Congress. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014471269/.

"The Works Progress Administration.” PBS. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/surviving-the-dust-bowl-works-progress-administration-wpa/.

"Works Progress Administration: Federal Music Project.” WNYC. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.wnyc.org/series/works-progress-administration/about.

"WPA Federal Art Project.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/WPA-Federal-Art-Project.

"WPA Federal Theatre Project.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/WPA-Federal-Theatre-Project.

Top photo collage: Training. Work Projects Administration (WPA) vocational school. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017693951/. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995, Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1013824907:2469?tid=&pid=&queryId=406cfece27eae887cac67e716bc35bbc&_phsrc=iHD41&_phstart=successSource&clickref=1100ljkAU4ZS%2C1100ljkAU4ZS&adref=&o_xid=01100l49xQ&o_lid=01100l49. 1940 U.S. Federal Census. Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-02660-00981?treeid=&personid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=HsD82&_phstart=successSource&pId=9615305.

Bottom photo collage: U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995, Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1006647777:2469?tid=&pid=&queryId=406cfece27eae887cac67e716bc35bbc&_phsrc=iHD41&_phstart=successSource&clickref=1100ljkAUd6g%2C1100ljkAUd6g&adref=&o_xid=01100l49xQ&o_lid=01100l49